1860-1864

1861 -62

LeGrand Lockwood sponsors “Firework on the Green,” Fourth of July fireworks in front of his Norwalk “summer” residence near St. Paul’s Episcopal Church during the summer of 1861 and 1862.

1862

Company F of the Union Army’s 17th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry is called “Lockwood’s Guards.” LeGrand Lockwood paid a bounty of $10 per man, for a total of $1,000; he also provided the men with heavy knit pea jackets and shirts for a cost of about $400 per soldier.

The Norwalk Gazette of Aug. 9, 1862 published an article entitled Make way for the Lockwood Guards!

LeGrand Lockwood has donated the magnificent sum of $1000 for the enlistment of another company of volunteers from Norwalk. Yesterday, Captain Fowler’s company was filled to its maximum number, and to-day large numbers of volunteers presented themselves for enlistment into his company, only to be disappointed. Lieutenant Enoch Wood has been commissioned by the adjutant general to recruit a second company. He is a military man of energy and character and proposes to take command, and he with is co-laborers in his recruiting service, Allen, Knapp, Kellogg, Lewis and others, are vigorously pushing ahead enlistments, and over fifty men are already enrolled. Ten dollars per man of the Lockwood fund is paid down as fast as sworn in.

LeGrand Lockwood elected Treasurer of the New York Stock Exchange for a one-year term; he is a member of the NYSE until his death.

1863

December: LeGrand purchases an additional 30 acres of land in Norwalk to build his country “cottage.” Acreage included the old homestead of James Benedict, adjoining plot owned by Charles Mallory, lying east of West Ave. “Public rumor names $1,000 per acre as the price paid, and the opening of a new street and the general beautifying and improvements of the grounds are among the objects contemplated by the purchase.”

1864

LeGrand Lockwood joins the Board of Directors of the Danbury & Norwalk Railroad as a major shareholder. The President of the Railroad is Edwin Lockwood, LeGrand’s uncle.

Construction of Elm Park Estate begins. Architect, Detlef Lienau, designs the Mansion and Lockwood will utilize the interior design services of the Herter Brothers, Leon Marcotte and George Platt.

1865-1869

1865

Lambert & Bunnell of Bridgeport is reported to be the architects of the estate’s Gate Lodge. The Norwalk Gazette reports in August that LeGrand Lockwood and his family will occupy the Gate Lodge that winter.

The Norwalk Gazette reports that William Trubee, the landscape gardener to P.T. Barnum, laid out the grounds of Elm Park and the “entire plot has blended into a romantic and picturesque whole;” Trubee is also the contractor for executing the porter’s Gate Lodge at the entrance.

1866

1200 ft. of wrought iron fence, manufactured by Waterbury & Duncan of Norwalk, is installed along the West Avenue boundary of estate.

1867

Aug. 5: The New York Times describes Legrand Lockwood’s Mansion as costing nearly two million dollars to build, and “when completed, will stand with scarcely a rival in the United States.”

LeGrand Lockwood commissions Albert Bierstadt to paint Domes of Yosemite for $25,000. This work was hung in the Rotunda of the Mansion. He also patronizes Jasper Cropsey, William Bradford, and Asher B. Durand, among other artists.

The Lockwoods travel to Europe, including Paris and visit the International Exposition of 1867, where they admire the work of Paul Balin, whose wallpaper is selected for the Mansion’s Library. They also visit Italy to purchase sculptures by American ex-patriot sculptors Joseph Mozier, Randolph Rogers, and Lucien Goldsmith Mead.

1868

The Lockwood Family moves into Mansion.

Whitney & Beckwith of Norwalk photograph Lockwood’s Elm Park, publishing stereoscopic views of the Mansion exterior, interiors and grounds. These photographs are of two nearly identical images of an object taken from slightly different angles. When viewed through a stereoscopic viewer the eye is either forced to cross or diverse and there is the illusion of a three-dimensional picture.

1869

Sept. 24: Black Friday, one of the greatest panics in American financial history, occurs. Price of gold drops causing scores of brokerage houses to be ruined, including Lockwood & Co.

Lockwood & Co. fails on Sept. 29 and declares bankruptcy on Oct. 1, leading to the loss of LeGrand Lockwood’s fortune. Lockwood is forced to mortgage the estate to pay back creditors. The gardening staff is relinquished.

Oct. 2: The New York Sun publishes an article, later republished nationally as “The Palace of a Ruined Banker,” which described the interiors and furnishings of Elm Park, including the Servants’ Quarters, and estate grounds.

LeGrand restarts Lockwood & Co firm, but sells $10 million worth of stock in the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railroad to rival Cornelius Vanderbilt; the mortgage on the Mansion was transferred from Union Trust to LSMSRR, thus to Vanderbilt’s control.

Oct. 4: LeGrand Lockwood resigns as Treasurer of Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railroad and is replaced by Vanderbilt underling James H. Banker.

1870s

1870

US Federal Census for Norwalk records that Lockwood had 9 servants (2 gardeners; 1 coachman, 1 cook and 5 house maids) living on the estate.

1871

Mansion and outbuildings are completed.

LeGrand Lockwood considers adding a “Palace Car”, or Drawing Room Car, on the Danbury & Norwalk Railroad.

1872

Feb. 24: LeGrand Lockwood, age 52 years old, dies of pneumonia in New York City.

Feb. 27: Rev E.P. Rogers delivers address for LeGrand Lockwood’s funeral at the South Reformed Church, Fifth Ave at 21st Street, New York City; funeral train travels from New York City to Norwalk for burial at Union Cemetery.

April: Auction of LeGrand Lockwood’s art collection at Leavitt’s Auction Rooms, New York City. Sale brought in “$43,190.00 with Bierstadt’s Domes of Yosemite only selling for $5,100. The painting is purchased for St. Johnsbury Athenaeum.

1873

December: Louisa Lockwood is unable to make the last mortgage payment of $90,000 and Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railroad, controlled by Vanderbilt, foreclosed on Elm Park.

1876

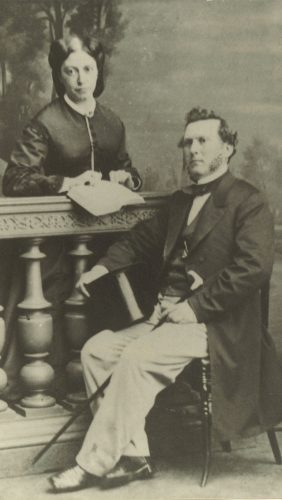

April: Charles Drelincourt Mathews purchases Lockwood’s Mansion for $100,000 as a summer retreat for himself, his wife Rebecca, their four children and grandchildren. The Mathews family continued to reside at the Mansion from spring to late fall until 1938.

July: Mathews family moves into Mansion. In her memoirs written in the 1930s, Florence Mathews recalls:

1879

May 23: Charles D. Mathews, age 58 years old, dies of a stroke at the Mansion.

Early 20th Century

1893-1896

Charles T. Mathews publishes The Renaissance Under the Valois (1893) and The Story of Architecture (1896). Both books were largely successful and used as textbooks at universities including Yale, Harvard, and Columbia.

1900-1906

Charles T. Mathews is selected to design the Lady Chapel at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, New York City. The first Mass in the Lady Chapel was celebrated on Dec. 24, 1906.

1909

Jun. 24: Lillie Mathews Martin dies in Norwalk.

1910

Rebecca Thompson Mathews dies in Norwalk. The Mansion is now in the hands of her surviving children: Florence, Charles T., and Harold.

1912

Harold C. Mathews’ mother-in-law, Helen Churchill Candee, a well-known and respected author, interior decorator, and women’s rights activist, survives the Titanic. She gives the first-published account of the tragedy, where she describes the events on Lifeboat Number 6 with American socialite and philanthropist, the “Unsinkable” Molly Brown. After arriving in New York via the RMS Carpathia, she retreated to the Mansion to recover from a broken ankle.

1934

Jan. 11: Charles T. Mathews dies in New York City.

1938

Aug. 16: Florence Mathews dies in Norwalk after living at the Mansion full time for four years with a full staff.

1939

Mathews Family leases Elm Park estate and Mansion to City of Norwalk for use as as a public park.

Mid-Twentieth Century

1941

Property purchased by City of Norwalk for $170,000. Used as emergency war-time offices and storage of heavy equipment.

1944

October: City of Norwalk runs hastily called auction of Mansion furnishings.

1950

Norwalk Redevelopment Agency begins urban renewal of downtown corridor. The Mansion is used for city offices.

1954

Estate barn demolished.

1955

Devastating floods strike Connecticut and Norwalk.

State purchases 8 acres of Mathews Park for U.S. I-95 construction. The Connecticut Turnpike (U.S. I-95) with its Norwalk tollbooth, were under construction from 1955-58.

1956

Mayor Cook plans to raze Mansion—“a useless white elephant of a building”— to build a city hall complex on the park, with the house foundation to become a reflecting pool.

City uses Mansion as “attic” for storage of books, tax records, voting machines and public works equipment.

1958

Police Court Building built on estate, replacing what had remained of the formal rock gardens, bowling green and ice house.

1960-1964

1961

City schedules Mansion demolition; Citizens unite and protest.

The battle to “Save Norwalk Mansion” was sparked by Elsie Hill, an indomitable lady in her late 70s, who roused citizens to band together. They sought to preserve the Mansion and make it a local museum and civic meeting space, while restoring the grounds as a public park.

Historic American Buildings Survey completed on Mansion with Cervin Robinson, photographing interiors and exteriors.

1962

Estate outbuildings demolished, estate blacksmith’s shop demolished, and greenhouse destroyed.

Common Interest Group of Norwalk, Inc. (CIG) formed to save the Mansion. The CIG appeals to city officials to preserve the Mansion in public hearings, and even forced the question to a citywide referendum. The vote: 8,632 for saving the Mansion and 6,124 against. CIG opens the Mansion to the public.

1963

Legal wheels turn as CIG organizes 16 taxpayers to sue the City of Norwalk over the city hall plans and Mansion demolition. Hasting W. Baker, et al. vs. City of Norwalk and John W. Gaydosh, was argued in Fairfield County Superior Court on Sept. 3, 1963.

1965-1969

1965

Connecticut Supreme Court of Errors ruled to preserve the Mansion and Veteran’s Park as a public space.

The Junior League of Stamford-Norwalk, Inc. signs a $1 a year 30-year lease with the City. The Junior League became the Mansion’s new tenant and on its docket was returning the “elegant but battered” house to its former splendor.

The Junior League Mansion Committee sets goal to reopen the Mansion as a house museum and begins making critical repairs (roof, window, masonry) to halt further decay and to make the house safe and usable (electricity, heat, security system).

State of Connecticut plans new Route 7 interchange to come within 138 feet of Mansion, taking 6 acres of Park. CIG fight successfully fights plan and interchange is moved slightly further away on property.

1966

The Lockwood-Mathews Mansion Museum of Norwalk, Inc. is established and assumes city lease on Nov. 28.

Fundraising for restoration begins: $100,000 raised from Charter Membership Drive, Candlelight Ball, Decorator Showcase and grants from the CT Historical Commission (c. 1968) to match 1970 HUD grant.

Aug. 28: The New York Times publishes article with headline, “Victorian Era Mansion Will Become a Museum.”

1967

Jun. 11: Mansion permanently opened to the public. The Junior League, with the newly created The Lockwood-Mathews-Mansion Museum of Norwalk, Inc., gives group tours on Sunday afternoons. Visitors preview the Mansion in its present condition and can envision the exciting possibilities of the future.

1968

“The Lockwood-Mathews Mansion has come through another exciting year. Its ‘past’ had been documented, its ‘present’ is being preserved and its ‘future’ is being prescribed.”— 1967-68 LMMM PROGRESS REPORT

July/August: Rufus K. Lerton publishes “The Lockwood Mathews Mansion” in CT Architect.

1969

First comprehensive history on the Mansion and LeGrand Lockwood is published, with Mimi Adams (Findlay) as editor.

Later Twentieth Century

1970

HUD awards Mansion $100,000 grant for preservation projects in urban areas.

A city without a sense of its past can have little hope of planning its future. For cities, like people, the heritage of the past can provide the identity and the place around which new commitments are made.

— GEORGE ROMNEY, SECRETARY OF HUD, 1970

March: Antiques Magazine publishes Margaret Donald Schaack’s article “History in Houses; The Lockwood Mathews Mansion,” the first national article on the Mansion’s history and significance.

The Mansion appears in the ABC television series “Dark Shadows” and feature film, “House of Dark Shadows.”

1971

Mansion designated National Historic Landmark, with a public ceremony and presentation of the plaque held in April 1972.

1974

Rotunda plasters restoration of cove and walls, with original stencil designs and paint colors uncovered and recorded.

The 62-room Mansion is a filming location for the film, “The Stepford Wives.”

1976

NPS/CT Historical Commission grant supports restoration of Entrance Hall and Vestibule plaster work; veneer and parquetry of Library and Rotunda floors; repairs to skylight and balustrade; and wainscoting of the Grand Staircase.

1978-80

Veranda and Porte-Cochere are restored and repainted.

1981

City of Norwalk grants 75-year lease to LMMM, Inc.

1982

Conservatory is rebuilt and re-glazed after damage from 1960s storm.

1990

Card Room restoration.

1997

Music Room plaster walls cleaned and repaired.

1998

Donations received of belongings and artwork owned by descendants of LeGrand Lockwood, Jr. and his wife Kate Bissell Lockwood.

Twenty-First Century

2000

Restoration of Library cornice and Entrance Hall mantel.

2001

Exterior original paint color samples taken and analyzed, then exterior repainted in original paint color.

2004

The Mansion used as set for the remake of “The Stepford Wives.”

2006

Candlelight Ball raises $50,000 to fund Scalamandre reproducing Library’s original embossed and engraved wallpaper that was originally designed by Paul Balin.

2012

Rotunda spandrel restoration.

2010

Library cornice restoration; ceiling cleaning and in-painting; woodwork cleaned and shellacked.

2015

State grant received for Servants’ Quarter’s restoration and ADA elevator.

2017

The Lockwood-Mathews Mansion Museum wins a Leadership in History Award, the most prestigious national award given by the American Association of State and Local History (AASLH), for the 2016 exhibition, The Stairs Below: The Mansion’s Domestic Servants, 1868-1938.

2018

ADA ramps are constructed at the basement-level exit points on the north side of the Mansion’s exterior. $5M state grant received for mechanical upgrades.

2020

The Museum wins the prestigious Award of Merit from the Connecticut League of History Organizations (CLHO) for the 2019 exhibition titled, From Corsets to Suffrage: Victorian Women Trailblazers.